This past Wednesday, May 14, while many in Massachusetts were preparing for hockey playoffs, or celebrating graduations from college, or merely enjoying the first breaths of spring, tragedy was front and center at the Massachusetts State House.

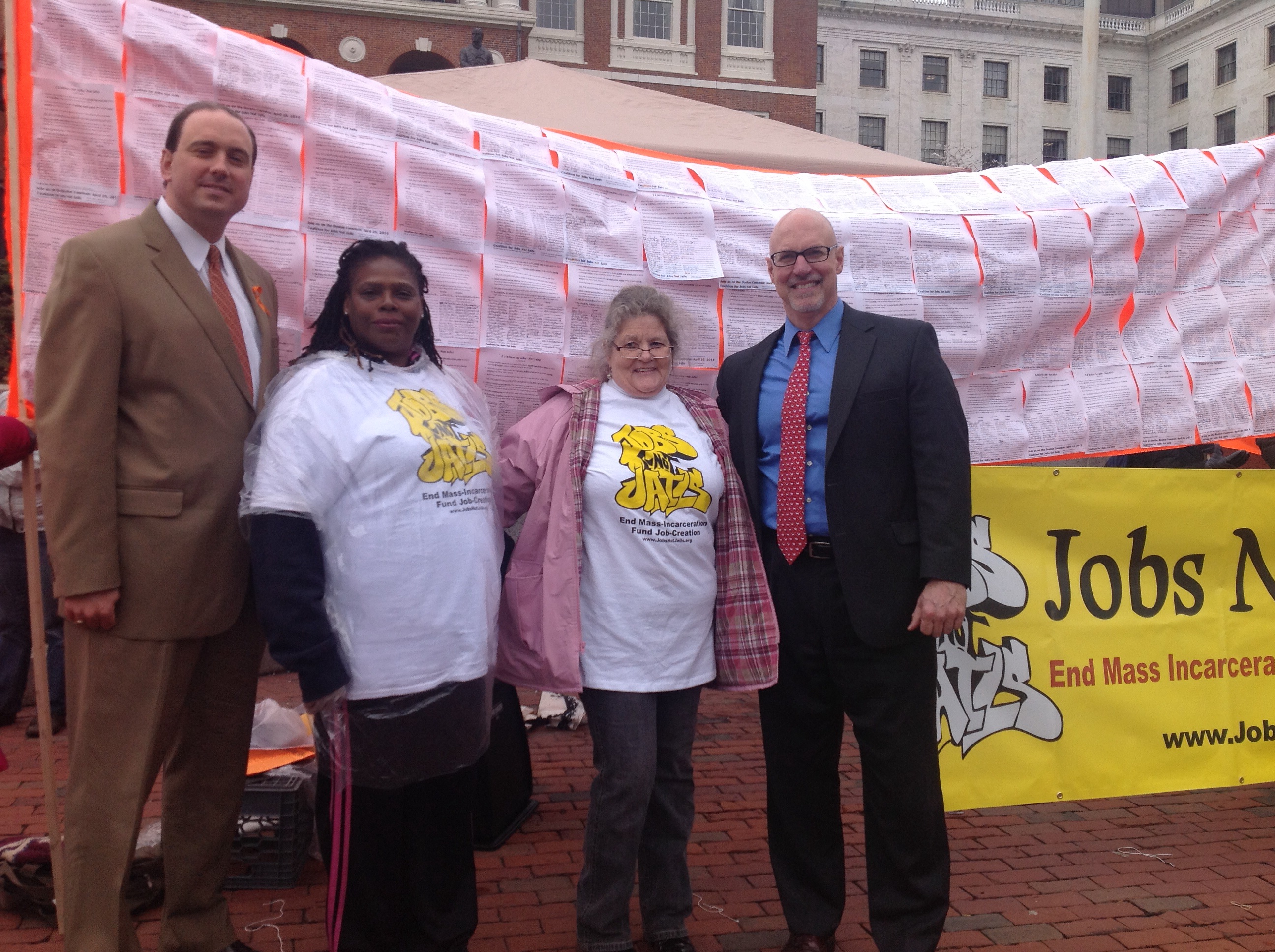

Barbara Kaban (left), Committee for Public Council Services (CPCS) and Tina Chery, Founder of the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute in Boston.

Barbara Kaban (left), Committee for Public Council Services (CPCS) and Tina Chery, Founder of the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute in Boston.

There, advocates, victims, elected representatives and officials came to testify about what to do with our juveniles who commit homicide—and although this is relatively rare, only twenty over the past thirty years said forensic child psychologist Richard Barnum in his written testimony—it is so awful to lose a loved one to murder that the outcry was understandable. Families who had experienced such losses spoke eloquently: “I dread Mother’s Day, a reminder of the day my mother was killed,” and “There is no parole from my loss.”

But Massachusetts is in for some difficult years of litigation if it follows the path of Senate Minority Leader Bruce Tarr who filed a bill setting a minimum of thirty-five years before any juvenile convicted of first-degree murder would be eligible for parole. This was in response to legislation passed this year in Massachusetts that ended the practice of life without parole for juveniles. The bill, S2008, would also set almost impossible standards for our Parole Board to consider such a youth rehabilitated—a potential minefield since the current Parole Board’s release rate has taken a nose dive, some would say, in response to public pressure. In Tarr’s bill, the Board gets no direction to consider factors such as what a prisoner has achieved behind bars, one of the most important principles in determining if someone is ready to be released on parole. The bill is overly harsh.

So why would this bill get us into trouble? Let’s go with legal issues first. In 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that across the country, juvenile life without parole could no longer be a mandatory sentence for youth convicted of first-degree murder, and declared that science had shown us that juveniles were different from adults. Such knowledge needed to be considered at sentencing. In 2013, Massachusetts went further, and as Barbara Kaban, Director of Juvenile Appeals at CPCS, said in her testimony, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) “determined that any death-in-prison sentence for a juvenile is disproportionate punishment in violation of the Massachusetts constitutional prohibition against cruel or unusual punishment.” Such juveniles need to have a meaningful chance at rehabilitation.

Tarr’s bill, gaining momentum after a grisly murder in Essex last year, aims to consider families, he said in his testimony before the Judiciary Committee. But if we do not put a stop to the idea of thirty-five years before parole, Massachusetts could face what Connecticut is facing. A former Justice of Connecticut’s top court, David M. Borden, wrote in an op-ed that his state had on the books a bill that would put it in compliance with the U.S. Supreme Court decisions. The House had passed it in full. He warned that without its passage in the Senate, they’d have “years of expensive and unpredictable litigation” and uncertainty for victims. The Senate let it die without a vote. Many of those in Massachusetts who submitted written testimony against Tarr’s bill cited that endless litigation over legal issues was a definite possibility because S2008 and another bill equally probematic, H.1426, do not seem to honor the spirit of the U.S. Supreme Court decision.

That list of written testimony against these bills was long, and included heavy-hitters such as attorney Bryan Stevenson, who represented the young people in the now-famous 2012 U.S. Supreme Court case I mention above, Miller v. Alabama. It included testimony from a number of youth-centered organizations that have experience with kids and have seen them grow and change; it included a former prisoner who had transformed his life, medical specialists, a former head of the Parole Board, judges, lawyers and youth advocates, as well as CPCS.

Most impressive was Tina Chery. Chery’s son, Louis D. Brown was murdered in 1994, and since that time, she has dedicated her life to helping address community violence.

Tina Chery’s son, Louis D. Brown.

Chery said that there are always two families to consider, the family of the one who was killed and the one whose child wielded the weapon. She said that families preparing to send a loved one to prison find themselves in a similar situation to the families of victims, but rarely receive the help they need to prevent future crimes. “Juveniles must be given meaningful opportunity to change,” she concluded, “and thirty-five years is not a meaningful opportunity.”

To that end, the bill seems based on the idea that juveniles cannot change. Joshua Rovner, State Advocacy Associate at the Washington DC-based Sentencing Project, in a telephone interview, said “A good bill gives an opportunity for individualizing cases and gives a Parole Board the opportunity to show rehabilitation. Opportunity for parole is not release.” He also pointed to Tarr and other members of the Legislature’s demand for thirty-five years before parole eligibility as “mis-characterizing” the requirements in the Supreme Court decision. While the Supreme Court called for individualized sentencing, Tarr’s bill rejects that, said Rovner, almost as if individualized sentencing somehow meant brevity.

Massachusetts should not have a knee-jerk reaction to this incredibly important subject (See Cinelli.) All too often we have made law based on our emotional reactions to tragedy. We should not make law based on emotion rather than on science. While the D.A. of Essex County and the president of the Massachusetts District Attorneys Association, Jonathan Blodgett, was one of the first to testify, he came armed with fury from the recent tragic killing in his county. While the horror his community felt at teacher Colleen Ritzer’s murder was justified, some of his claims were not. He said that brain science is an “evolving science…a very slippery slope.” But certainly, this sounded like the dispute over climate change, and scientists who have spent their lives studying the brain would sharply disagree with Blodgett. For years we have known that juveniles are not adults developmentally, emotionally, and psychologically. Researchers such as clinical scientist, Antoinette Kavanaugh, say adolescent development based on neuroscience shows that kids are different from adults. She insists that techniques like Functional Magnetic Resonance Imagining that are used in brain research are not “new” or “evolving.” The evidence is there and not going away.

So how do we get out of this mess? We might take our lead from other states that are using this as an opportunity to think more deeply about juvenile justice and not react precipitously. Rovner pointed out that twenty-eight states including Massachusetts were affected by the Miller ruling; eight states plus DC had previously banned juvenile life without parole (JLWP), and interestingly this includes Montana, Texas, and Kansas—i.e. not a blue/red divison; fourteen states had allowed JLWP. But not all used it, including New York, Maine, and Rhode Island. Rovner said it is also not uncommon for states to seek retroactivity so that those already serving first-degree sentences can come up for parole hearings—Massachusetts has 63 such cases. Texas, Illinois, Nebraska, Iowa, and Mississippi all have sought relief for prisoners already sentenced, i.e. retroactivity.

West Virginia has a law that we might turn to for guidance. When a sentence is issued to a juvenile convicted of life, the Court must consider what are called the “Kagan factors,” based on what Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan said during the famed Miller v Alabama hearing: “(1) Age at the time of the offense; (2) Impetuosity; (3) Family and community environment; (4) Ability to appreciate the risks and consequences of the conduct; (5) Intellectual capacity; (6) The outcomes of a comprehensive mental health evaluation…; (7) Peer or familial pressure; (8) Level of participation in the offense; (9) Ability to participate meaningfully in his or her defense; (10) Capacity for rehabilitation; (11) School records and special education evaluations; (12) Trauma history; (13) Faith and community involvement; (14) Involvement in the child welfare system; and (15) Any other mitigating factor or circumstances.”

And in West Virginia, prisoners sentenced as youth are allowed meaningful chance at rehabilitation and parole eligibility after fifteen years.

The Statehouse News reported that Gov. Deval Patrick had filed his own bill with a twenty-year minimum before parole consideration. This is better than thirty-five years but it still seems to play into the idea that children are similar to adults. Bob Gittens, a former prosecutor, Department of Youth Services commissioner, and Parole Board chair under Gov. Michael Dukakis, testified at the hearing that he fears for an “institutionalization” of children who go into adult prisons, making it more difficult for them to change, and he believes that our parole policy should not be “a one size fits all.” He is concerned about juveniles serving twenty or twenty-five years. “Sooner than later” was his advice.

Gail Garinger, the child advocate for the Commonwealth and a former juvenile judge left the Judiciary Committee with four factors to consider as they deliberated on how to proceed:

*Respect gravity of the offense;

*Public safety: her experience has convinced her that most juveniles can mature into good citizens;

*Regarding the capacity of young people to grow, mature and change, she said, “We cannot give a broad brush stroke to murder and cannot enact a law that only responds to the most horrific acts;”

*Costs associated with incarceration.

Striking the right balance is difficult but Garinger said she thinks fifteen years is the right balance to start seeking parole. She also urged that first degree murder jurisdiction for juveniles be returned to the juvenile court.

And certainly, that’s another important story.