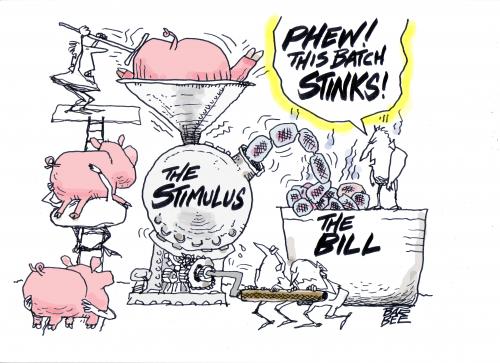

Philip Chism’s alleged murder of Colleen Ritzer may have added fuel to the fire, but legislative sausage-making is about to bring us a new juvenile sentencing law.

Photo via barfblog.com

Massachusetts Juvenile Judge Jay D. Blitzman got it right when he wrote in Gault’s Promise “As the public and media react to the crime du jour, there is an unfortunate tendency to legislate by anecdote.” Bad cases can lead to bad laws.

Less than a year after the tragic death of Colleen Ritzer by the alleged fourteen-year-old killer, Philip Chism, this week or next, the Governor is expected to sign into law: “An Act relative to juvenile life sentences for first-degree murder.” Some are wondering if this will prove another rash reaction to the grief and anger over horrendous crimes (see Cinelli) —not the science and reason needed to make good legislation.

The Bill, a concoction from the House and Senate, is an attempt by the Legislature to respond to two recent high court rulings. In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark decision, Miller v. Alabama. Miller said science had proven juveniles were different from adults; they needed a judge’s thorough consideration, case by case, and could not automatically be sentenced to life without a meaningful chance at parole.

Then in 2013, Massachusetts’ Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) went further in its interpretation of Miller with the Diatchenko v. District Attorney decision. The SJC struck down all sentences of life without parole eligibility for juveniles. This made sense; no other country allows juveniles to live behind bars until they die. A Massachusetts juvenile first-degree lifer was to serve at least 15 years before parole eligibility— a number deemed to allow a meaningful chance at rehabilitation.

But the new law, if signed as is, will be harsher than Diatchenko (and harsher in some ways than the one Governor Patrick first filed in 2013 where he set a minimum of fifteen years for juvenile first-degree lifers). It provides for initial parole eligibility at 20-30 years in felony murder cases — i.e. you were there but didn’t pull the trigger. It requires 25-30 years in cases of premeditation — i.e. first-degree murder; and it sets a mandatory 30 years for extreme cruelty and atrocity (EAC).

Rep. John Keenan (Salem) who filed a bill in 2013, prior to the Chism case, but hails from the district next to Danvers where Colleen Ritzer was murdered, wanted 35 years before parole eligibility. Keenan said his bill was in response to Miller, and feels the new law will be a “solid compromise — it pays respect to victims and to the nature of juvenile minds.”

However, according to a brief written by attorneys Patty Garin and Dave Nathanson in 2011, EAC “encompasses almost all violent murders.” 30 years, they say, is in essence, a de facto life without parole sentence. And they and other activists say the bill of Patrick’s desk ignores the mind of a child as discussed in the recent court cases and a meaningful chance for rehabilitation.

If fourteen-year old Chism is convicted of 30 years, he would be sentenced to almost twice the number of years he has lived before getting a chance to see the Parole Board — with no guarantee of release.

Naoka Carey, Executive Director of the advocacy group, Citizens for Juvenile Justice, said in an interview that the Legislature, “in a sense, felt that they had to do something after Diatchenko.” Families of victims experienced Diatchenko decision as “somehow too light for their grief—they felt the ground shifted underneath them,” she said. “This happens when constitutional decisions get interpreted. Most of the time, we recognize that kids are different but when they do terrible things, we forget.”

Sen. James Eldridge (Acton), one of four in the Senate and eighteen in the House who voted against the bill, agrees. He said in an interview, “A horrific murder pressures, pushes people to be tough on crime.” He pointed out that the amendment passed by the Senate with a right to counsel was ultimately not in the final version of the bill.” While gladdened with some options for juvenile lifers — eligibility for education and treatment, and no maximum ten-year wait if a juvenile lifer is refused parole— said sentences are too harsh and that “there was little discussion about the distinct nature of juvenile development.”

This past May, many families of murder victims who wanted no juvenile first-degree lifer to ever get parole, descended on the State House with 15,000 signatures decrying the ruling in Diatchenko. Chism’s case only added fuel to their fire.

There is already talk of litigation to determine what Diatchenko requires and to sort out the mishmash; if the Governor does sign it, this new law is likely to end up in the courts.